Digging Dangerous Data | Ashley Madison & the Archaeology of the Now

Introduction

In July 2015 a large amount of data was stolen

from Ashley Madison,

an online business dedicated to facilitating people who sought to have

extramarital affairs. The hackers who stole the data, calling themselves ‘The

Impact Team’, attempted to use it for blackmail, insisting that Ashley Madison

and fellow Avid Life Media site EstablishedMen.com be permanently shut down. On

June 22nd, when the company failed to comply, a sample of the data was released

publicly. Obviously, negotiations didn’t go as well as might have been hoped

and in August the full dataset was made available on the internet. Late in the

same month a further data dump was made available that included a number of corporate emails, including a substantial number from CEO

Noel Biderman. Since that time, it is believed that a number of

enterprising petty criminals have attempted to use the Personal Identifiable

Information (PII) to blackmail alleged account holders.

Let me be clear. There are tangles of legal,

ethical, and moral arguments in every sentence and clause in the above

paragraph. I don’t hope to offer a solution to any of these … not one! If you

think that you can deliver an all-encompassing answer or firmly-established response to any aspect of this in a

few sentences, you’ve not thought about it enough - you really haven't. In some respects, all these

conversations are academic – the data now exists in the public sphere. The

initial data dump was made to the so-called ‘Dark Web’ Tor Network that can

only be accessed via a specialised browser via an encrypted connection routed

through a number of proxy services. However, the files quickly migrated to bittorrent,

a peer-to-peer transfer protocol. As Alex Hern explains in The

Guardian: 'The file is broken up into multiple blocks, which are then

shared directly from one downloader’s computer to the next. With no central

repository, it is all but impossible to prevent the transfer, although a

“magnet” link – a short string of text telling a new downloader how to connect

to the “swarm” of files – is still required'. To cut through the technobabble:

whether or not you like it, hate it, are embarrassed by it, or whatever – this

is data that is not going to go away. As Wikipedia reports: ‘The

parent company Avid Life Media, which owns the site, has offered a reward of

C$500,000 (£240,000) for information about the Ashley Madison hackers.’ So

what? … Once that the

cops have chased after and caught ’em … they’re punished, they go to jail …

and the data is still there, available to everyone who wants it. Private

Bradley Manning (now Chelsea

Manning) stole something in the region of 750,000 classified and sensitive

documents relating to the US military and diplomatic organisations. In 2013 she

was sentenced to 35 years for violations of the Espionage Act and will be

eligible for parole in 2021. But the documents, passed on to WikiLeaks, are still freely

available. With regard to both instances, there are questions about the

legality and morality of collecting and disseminating the data, but they really

matter little terms of the fact that, once released, it can’t be erased or

eradicated. There is no getting this genie back in the bottle.

Now that the Ashley Madison dump is available,

what are we going to do about it? And by ‘we’ I mean archaeologists and

historians. It may seem counter intuitive, but this is pure archaeology and

history territory. If you think that historians are only properly employed in

dusty archives, searching through government documents, you don’t understand

the range of what their skills can be applied to. By the same token, if you

think that someone can only be a ‘real’ archaeologist if they’re covered in mud,

carefully uncovering a decorated pottery vessel before the bulldozers track in

and destroy the lot, you’re equally mistaken. These are both aspects of what we

do, but neither goes anywhere to encompass the totality of what either

profession actually does or can achieve. In essence, both are really about using available data to tell

stories at varying scales – from the individual, to countries, to continents.

More importantly, both are adept at assessing the quality of and bias in data …

basically, we were made for this data and this data was made for us! When the

archaeologies and histories of the 21st century are written they will have to

incorporate WikiLeaks data if they are to fully understand certain aspects of

military and diplomatic events and relationships. In the same way that Cabinet

papers released under the thirty-year rule can

give a profoundly different insight on public actions and statements, these

documents will change how we see historical events. While we’re, generally, a

bit more prudish when it comes to stuff involving genitals, the Ashley Madison

data is going to be just the same – no self-respecting historian of the future

is going to be able to talk about early 21st century society without dealing

with this data dump. On top of all that, it’s likely that stolen data dumps

will only increase in size and frequency over the next decades and, thus, in

importance for future researchers. This feeling is reflected in one of the

statements by Avid Life Media, saying that this form of

hacking and dumping ‘may now be a new societal reality’. Still not convinced?

Let me put it another way … what if we excavated a data source that gave

information on some aspects of the sex lives of individual builders of

Stonehenge or Newgrange? We’d be all over that like a shot!

Archaeologists in particular have a love of chronology and location and the Ashley Madison data has both in spades … the only difference is that their relative qualities are inverted. It’s usual on a regular archaeological excavation for the chronology to be a bit imprecise, but the location is well tied down and understood. For example, the pottery sherd came from this particular layer in that portion of the ditch on the site that is at that location in this country ... but the radiocarbon date on the charcoal from the same layer gave a range of 60 years. Seem familiar? Here the situation is that we can’t always be sure if the name attached to the account really relates to that specific person in that specific town (more on this later), but we can tie transaction data down to the second. In every real respect, this is data eminently suited to analysis by archaeologists and historians. The only real difference is the passage of time … and even this isn’t as much of a consideration as it might appear. Not too long ago the general working practice in parts of the UK was to machine off the Medieval remains to get to the more important Roman stuff … then that changed and we only machined off the post-Medieval to get to the Medieval, and now that too has changed. A little over 10 years ago I was working on the excavation of a brickworks that went out of business in 1922. Between the famously divisive ‘Transit Van’ excavation and work like Andrew Reinhard’s Atari video game burial dig, the age of what is considered to be ‘acceptable’ for the interests of archaeology and archaeologists has been brought closer and closer to the present time. All I’m proposing is that we change the scale from a couple of decades to a couple of months.

Archaeologists in particular have a love of chronology and location and the Ashley Madison data has both in spades … the only difference is that their relative qualities are inverted. It’s usual on a regular archaeological excavation for the chronology to be a bit imprecise, but the location is well tied down and understood. For example, the pottery sherd came from this particular layer in that portion of the ditch on the site that is at that location in this country ... but the radiocarbon date on the charcoal from the same layer gave a range of 60 years. Seem familiar? Here the situation is that we can’t always be sure if the name attached to the account really relates to that specific person in that specific town (more on this later), but we can tie transaction data down to the second. In every real respect, this is data eminently suited to analysis by archaeologists and historians. The only real difference is the passage of time … and even this isn’t as much of a consideration as it might appear. Not too long ago the general working practice in parts of the UK was to machine off the Medieval remains to get to the more important Roman stuff … then that changed and we only machined off the post-Medieval to get to the Medieval, and now that too has changed. A little over 10 years ago I was working on the excavation of a brickworks that went out of business in 1922. Between the famously divisive ‘Transit Van’ excavation and work like Andrew Reinhard’s Atari video game burial dig, the age of what is considered to be ‘acceptable’ for the interests of archaeology and archaeologists has been brought closer and closer to the present time. All I’m proposing is that we change the scale from a couple of decades to a couple of months.

The data

dump

With that in mind, it’s probably appropriate that

we examine what the data dump (the ‘site’) actually holds and how it is

structured. The 9.7Gb compressed archive (I've not accessed the 20Gb email dump) contains the site’s a large amount of

internal corporate data along with the user database. The latter contains users

profile information, including names, street addresses, and birth dates. There are lists of personal details including

data on whether the user smokes or drinks and the type of individual they’re

hoping to encounter, along with their preferences in terms of sexual desires

and the acts they’re willing, interested, or able to perform (via Alex Hern, The

Guardian). The majority of interest has centred on the portion of the

database that holds users email addresses as it is significantly easier to

search and interrogate than other portions of the dump. Much has been made of

the fact that addresses in the US and UK military along with a variety of

companies and seats of learning have all appeared in the database. As Hern and

other commentators point out, as much fun as this is, this is a relatively

unreliable means of assessing who had an account. In the first instance, Ashley

Madison did not require that an address be validated before it could be

associated with an account and thus there are multiple cases of patently false

email addresses in the data. The Wikipedia

article on the data breach notes that ‘people often create profiles with

fake email addresses, and sometimes people who have similar names accidentally

confuse their email address, setting up accounts for the wrong email address.’,

before going on to note that accounts could have been set up as part of office

pranks. As an aside, I’d just note that if you work in a place that considers

creating a fake account with an infidelity facilitating website an appropriate fun endeavour, you work with

asshats and need to find another job! Herne’s piece in The Guardian briefly

mentions that a further portion of the database contains details of credit card

transactions, but does not include sufficient information to steal cash.

The next aspect I’d like to very briefly touch on

is the business

model used by Ashley Madison. It seems that, unlike many other dating and

hook-up sites, Ashley Madison does not require a monthly subscription to keep

an account active. Instead, they set a credit cost for men to open chat

sessions and send messages to women. It also charges for men to read messages

sent by women. There’s a premium rate for men to have a guaranteed affair, and

even more money can be spent on sending gifts of animated gifs etc. From what I can gather, the only

people paying for anything are men.

Colin Gleeson, writing for the Irish Times on July 21st, notes that

‘Figures released by the website in 2011 said there were more than 40,000 Irish

members. However, a graphic called “the global infidelity map”, published on

the website’s Twitter account a fortnight ago, outlined its per capita

membership in countries around the world. It indicated that 2.5 per cent of the

Irish population were members, which equates to approximately 115,000

individuals.’ He also notes that this data indicates that Ireland ranked 10th

of the 45 countries with access to the Ashley Madison site. Again, more on this later ...

The Credit

Card data

So, who’s using this data and to what ends? As

you’d expect, other than the attempted blackmailers, the first ones to pick

over the data have been journalists

looking for a salacious titbits and they’ve certainly found them. Among the

most high profile of those outed is the reality TV ‘star’ Josh Duggar

(if you’ve never heard of him, be grateful – your life is a better place for

it). While I care little for him or his particular views on religion and

politics, I’m of the opinion that nothing good can come from shaming people –

both the private individuals and the vaguely famous – though that’s not stopped

the practice! Annalee Newitz at Gizmodo

has been doing some excellent technical work analysing the source code,

specifically seeking to understand how ‘bots’ (fake profiles) were used to chat

to users and (allegedly) relieve them of cash for the privilege, when they

thought they were talking to real women. Data Scientist Zack Gorman published

an Ashley

Madison Users By Zip Code map on Tableau Public, but only using data for

the US (excluding Alaska & Hawaii), though he received some criticism

from Reddit users for his actions.

Right now we’re in a situation where the analyses being

carried out are either exclusively concerned with the US, B-List celebrities,

and the prevalence of fake ‘bot’ women. Other than shaming individuals, I’ve

got no problem with this … it’s just that while the Irish Times have made some general statements on the topic, there

appears to have been little if any attempt to see what the data means for the

UK and Ireland generally. It also appears that no one has attempted to use any

of the financial data available in the dump to see what light it sheds on our

society. As noted above, Alex Hern’s piece in The Guardian mentions ‘a database

of credit card transaction information’. I’m not sure if he’s looking at the

same data I’m looking at, but what I see is not a database. It’s a collection

of 2642 .CSV (comma

separated values) files covering the period from March 21st 2008 to June

28th 2015 - by my quick calculation, this indicates that records for only 13

days are missing – pretty dashed comprehensive! Each one appears to represent

the totality of the day’s credit/debit card transactions and, I surmise, is a

daily download for use in Ashley Madison’s Business Intelligence environment of

choice. The reason that they appear to have been ignored until now is that

while they are individually easy to work with, their sheer volume means that

they take significant effort and energies to sort, search, and collate. As one commentator

on Reddit says: ‘to search for a single name in the CC files would be

something that would take a lot of time and effort. They are individual files

per date, over years, not easily searchable’. But that is exactly what I’ve

done. Even if opening each file, filtering the data for British and Irish

material, copying it to a master file, and closing it down again only took 20

seconds, the whole procedure would have taken me a little under two working

days … which is another thing to note about those of us with an archaeological

background – we’re tenacious! As numerous commentators have noted, using the

dump of account details and email addresses is fraught with problems. These

include the free accounts set up by the curious who never progressed with their

involvement, those who had accounts deliberately or accidentally set up in

their names, or even spouses wanting to verify if their partners were already

users of the site. On the other hand, I would argue that if you’ve actually

gone so far as to spend money on the services offered, chances are that you’re

pretty committed to the notion of infidelity. It is my opinion that – so long

as these files are genuine – this is the most accurate and honest way of

assessing involvement and participation in the site … and we’ve every reason to

believe that these are genuine, including statements by Ashley Madison

themselves.

Credit Card

Data Structure

The first thing to explain is how these files are

structured. The 2642 .CSV files range in size from 15Kb to 3.4Mb. While there’s

variation, and it’s far from being a continuous and unbroken upwards

progression, it really does show how the company expanded and grew during the

period under review. Early files have only a couple of thousand lines of data

and are confined to the company’s core US and Canadian markets. At the other

end of the range, the data frequently exceeded 10,000 to 12,000 data rows,

representing transactions from most (if not all) of the 53 countries

where the company was active. Even if we only graphed the file sizes of each

.CSV document we’d have an eloquent testimony of how the company grew and

expanded over this period. Whatever the size of the documents, the internal

format and layout was always the same. Going by column they were:

Column A:

ACCOUNT

This is the account number into which the money is

being paid. There are 41 different account numbers each from eight to 10 digits in length.

Column B:

ACCOUNT NAME

Again – pretty simple. This is the name associated

with the account number (above). Ashley Madison and parent company Avid Life

Media (ALM) don’t just have one website and one service. Apart from the main AM

site, the same company also runs EstablishedMen.com. In the British and Irish

data there are 41 Account Numbers associated with 26 different Account Names. It

appears that each Account Name can have multiple Accounts. The Account Names

include variations on ADL Media; AMDA; Ashley Madison; Avid Dating Life; CL

Media; EM Media; and Swappernet. AMDA is probably not the American Musical and Dramatic Academy, but CL

Media would appear to refer to CougarLife, a site for younger men to meet older women and

EM Media is almost certainly EstablishedMen, the site for helping younger women

meet older men. Swappernet is just what you think it is … if you have no idea

what it is I can only reiterate Bartleby’s address to the female board member

in Dogma ‘You,

on the other hand, are an innocent. You lead a good life. Good for you.’

Column C:

AMOUNT

This is the amount of money paid from a

credit/debit card to Ashley Madison. There is no indication as to the currency

that this is calculated in, but as ALM is a Canadian company, I’m presuming

that it’s in Canadian Dollars (C$).

Column D:

AUTH CODE

The Authorization

Code is issued by the credit card holder’s bank to indicate that the charge

has been approved. These codes are usually six or seven digits in length and

can be either alphanumeric or plain numeric. Crucially, these codes are only

issued when the charge has been approved. Thus, we can be certain that the

amounts listed as charged were approved and were paid to Ashley Madison. The

only exception to this is when the merchant takes payment without the

authorisation code. If an authorization code is not issued, the merchant can

receive a "no authorization" chargeback. In a chargeback, any payment

the merchant receives is reversed by the card issuer (via eHow).

Column E:

AVS

This is the Address Verification System. This is a

system used to verify the address of a person claiming to own a credit card.

The system will check the billing address of the credit card provided by the

user with the address on file at the credit card company (via Wikipedia).

From what I can see, this field will be populated if the Authorisation Code

(Colum D) is populated, but will be blank if the Error Code (Colum P) is

populated

Column F:

BRAND

The Brand refers

to the type of card that was used to make the payment. Each credit/debit card

company is represented by an abbreviation. For example, VI represents Visa, while MC

(unsurprisingly) stands for MasterCard.

Column G:

CARD ENDING

These are the last four digits of the member’s

credit card number. I have not conducted any analysis on these and I do not

intend to discuss them further.

Column H:

CVD

The CVD is the Card Verification Data

– the three digits on the back of your card. It is used in ‘card not present’

transactions and was instituted to assist in the fight against card crime. No

actual CVD numbers are present here, merely the list of returned transaction

codes. Visa and MasterCard, for example, use M for ‘Match’, N for ‘No Match’

and Y for ‘Non Applicable’. American

Express, apparently wanting to be a bit different, went with M for ‘Not

Applicable’ and Y for ‘Match’ (via Chase).

I have not conducted any analysis on these and I do not intend to discuss them

further.

Column I:

FIRST NAME

This one should

be easy. This one should contain the

first name of the payee. SHOULD … but doesn’t always. True, there are a number

of cases where this field is populated by a recognisable first name, but these

are the minority. Instead, this column is mostly filled with five to seven

digit numbers. In the absence of better understandings, I’m presuming that this

is actually the user’s membership number. I’ve used the ‘first’ and ‘last’

names in the following analyses to ensure that when I’m examining data at the

individual-level that it is consistent and actually relates to the same

individual/account.

Column J:

LAST NAME

This column sometimes contains a surname when the

first name is in the previous column. Sometimes it’s blank (especially in the

earlier data). More often than not it contains the full name or pseudonym of

the user. Like the data in the First Name field (Column I) I’ve used it as a

visual reference to ensure that individual-level data is correct, and I've created a concatenated field of First and Last Names to create unique account identifiers. These have been used to clearly separate out user data, but at no point are names or pseudonyms referred to in the text.

Column K: MERCHANT

TRANS. ID

The Merchant Transaction ID is a seven or eight

digit code (I think) produced by the merchant (Ashley Madison in this instance)

to identify each purchase. In a minority of cases this is populated with an

alphanumeric, frequently including the words ‘Premium’, ‘Priority’, ‘Refund’ …

sometimes in combination. I have not conducted any analysis on these and I do

not intend to discuss them further.

Column L:

OPTION CODE

This column is blank for all of the British and

Irish data. I have not conducted any analysis on these and I do not intend to

discuss them further … obviously …

Column M:

DATE

The date is given in the format: Day/Month/Year

Hour: Minute: Second (e.g. 28/03/2008 00:51:22). No archaeologist has ever

worked with better chronological data than this! The only issue I have not been

able to work out here is which time zone this is tied to. As Ashley Madison

have their corporate

headquarters in Toronto, it seems plausible that their systems would use

local time - Eastern

Time Zone (UTC-5:00), but I can’t be certain.

Column N:

TXN ID

The Transaction ID is, essentially the ‘proof of

purchase’ for the user. In the current data set they are usually nine to 10 digit

numbers. In a minority of cases the ID is a 36 character alphanumeric and appears

to correlate with an alphanumeric Merchant Transaction ID. I have not conducted

any analysis on these and I do not intend to discuss them further.

Column O:

CONF. NO.

I presume that this stands for Confirmation Number

and is a seven to 10 digit number. From a quick check of the data, it appears

that this is usually identical to the data in the TXN ID Column (Column N).

Within the current data set, only 150 entries do not show a match between TXN

ID and Conf No and these appear to correlate to instances where the Merchant

Transaction ID is an alphanumeric. I have not conducted any analysis on these

and I do not intend to discuss them further.

Column P:

ERROR CODE

In the vast majority of cases this field is blank

as the transaction processed without any error. However, at the bottom of each

file there is a portion where uncompleted, failed, or stalled transactions are

collated. While a transaction in this section will frequently have most of the

rest of the data in place, it is unlikely to have an Authorisation Code (Column

D) and an AVS code (Column E). Some may not have a pass flag for the CVD check

(Column H). A collaborator on this project informs me that these codes are

unique to individual merchants and may relate to various reasons why the

transaction failed or was declined. For instance, the AVS check examines the

address associated with the card and the user. Ostensibly, this is to prevent

fraud, but based on some of my visual examinations of the data may occasionally

be due to incorrect home addresses being entered into the system. This may be

due to genuine errors or may stem from attempts by users to conceal their real

world location and failing. Other reasons for transactions to error out may be

fraud blocks put in place by the card holder’s bank or lack of funds/credit.

Column Q:

AUTH TYPE

The options for what I presume is the

Authorisation Type are either ‘Final’ or ‘Undefined’. I have not carried out

any further analysis of this data.

Column R:

TYPE

The transaction type may be one of five:

Authorisation, Settlement, Chargeback, Credits, or Purchases. The most

important thing to note here is that most of the data is composed of paired

lines. By this I mean that there is one line representing the Authorisation to

take the money and a separate line indicating the Settlement. A visual

examination of the data indicates that all the other fields (e.g. Account, Amount, Names, Merchant

Transaction ID etc.) will be

identical, except that one line is flagged as Authorisation and the other is

Settlement. Within the current data set there are 27,200 Authorisations and

25,590 Settlements. My presumption is that not all of the Authorisations

progressed to Settlements and, thus, when talking about the amount of money

spent, I’ll be omitting the Authorisation data. Purchases are a bit odd … there

are 10,593 lines flagged as purchases, but all are associated with error codes

of one kind or another. I freely admit that I have no idea why this is, and

I’ve excluded them from any further discussion of the amounts of money paid. In

almost all cases Credits are associated narrative entries in the Merchant

Transaction ID that indicate that they are refunds, some of these are

specifically indicated to be the result of fraud. As noted previously,

Chargebacks are where Ashley Madison – for whatever reason – incorrectly took

money from an account and later had to pay it back.

Column S:

TXT_CITY

In every .CSV file Column S is called

‘TXT_CITY%2CTXT_COUNTRY%2CTXT_EMAIL%2CTXT_PHONE%2CTXT_STATE%2CTXT_ADDR1%2CTXT_ADDR2%2CZIP%2CCONSUMER_IP’,

but it is clear that the ‘%2C’s are intended break up the titles for multiple

columns. As the title indicates, this is the member’s city of residence.

|

| Lines of data for UK & Ireland |

Column T:

TXT_COUNTRY

For all of the Ashley Madison data, this is given

as a two letter identifier code for the country. Ireland is indicated by IE and

the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Scotland, & Northern Ireland) is given

as GB. This has been my primary field for data selection. I’ve filtered the

original .CSV files to only show IE and GB data, then selected and copied the

data to a separate file. I’ve removed any data lines that are obviously errors.

For example, one recurring purchaser always appeared to identify his country as

IE, but the city was in the US. As his email address referenced the American

Football associated with said city, I felt justified in removing him from the

data set. However, there may be more included that should not be there. The

other side of this is that British and Irish patrons that deliberately or

accidentally identified as coming from another country have been overlooked and

are not included in this analysis. While this is regrettable, it is my opinion

that they make up a relatively insignificant portion of the overall group.

Column U:

TXT_EMAIL

This field contains the email address of the

member. While I’ve not used this data in these analyses, it is clear that this

column contains wide variety of obviously fake email addresses along with many

that, at least appear to be, genuine. Much has been made of the various email

addresses of government and university sector workers that appear to have

signed up, but as Ashley Madison did not appear to require email verification

it is best to treat all addresses here with some degree of suspicion.

Column V:

TXT_PHONE

The phone number of the member. As there are only

two numbers used for all of the British and Irish data: 12121212 and 111222333,

I think it’s safe enough to regard them as fake. They have not been used in these analyses.

Column W:

TXT_STATE

Presumably intended mostly for US customers, the

British and Irish data contains a bewildering array of two and three letter

acronyms; full and abbreviated county names, country names, even a few ones

just composed of numbers. I’ve not examined this data in any depth.

Column X:

TXT_ADDR1 and Column Y: TXT_ADDR2

These contain the addresses of the site’s clients.

Again, there’s a variety of data captured here, and not all of it can be

accepted at face value. The data varies from numeric (1-6 digits), gibberish

alphabetic and alphanumerics, and obviously/likely fake addresses, though the

vast majority are ostensibly real/plausible addresses. Indeed, the combined

geographical and personal data is frequently coherent and sufficient to

identify individuals with a reasonable degree of certainty. I’ve only used this

data to attempt to ‘weed out’ occasional entries that have been miss-assigned a

country code.

|

| UK & Ireland valid transactions |

Column Z:

ZIP

The data here ranges from a variety of obviously

faked alphabetic, numeric, and alphanumerics. The Irish data includes various versions

of Dublin postcodes, but also town and county names and country designations.

Interestingly, there are a small number of postcodes beginning with BT,

indicating a Northern Irish origin. I would note here that it’s bizarrely

saddening to see that sectarian divides are still prevalent, even on a site

devoted to infidelities. I’ve seen a number of Londonderry’s that are in GB,

and a few Derry’s in IE and I've considered each to be of the country they claim and have not altered the data. With regard to the UK, the data does appear to be

dominated by valid (or valid looking) postcodes. I’ve entered a few into Google

Maps and most return real-world locations, though that is no guarantee that the

transactions refer to these exact places. Beyond these few manual checks, I

have not used this data in these analyses.

Column AA:

CONSUMER_IP

My guess is that this data was collected

automatically by the Ashley Madison system, where available. IP addresses

feature relatively frequently in the data, but I’ve made no use of them.

Preliminary

Data Analyses for the Republic of Ireland and the UK

Having copied all the relevant data I can find

into a separate spreadsheet (and attempting to remove incorrect entries where I

can spot them), I’m left with 63918 rows of data. Of these, 6,075 relate to

Irish transactions, while 57,843 are associated with UK accounts. But these

numbers only refer to account activity and payment transactions. What we really

need is to get an idea as to how many active accounts there actually are. Colin

Gleeson’s piece in the Irish

Times gives figures of 40,000 and 115,000. I’m not saying that there are

not 40,000 Irish people who’ve signed up to a free account out of curiosity or

genuine intent. What I can tell you is that there are 1251 accounts that

identify as Irish (including a number from Northern Ireland) that paid actual

money to Ashley Madison. There are also 2501 accounts of UK origin (also

including a number from Northern Ireland). Obviously, there is a question of

where is a question of where infidelity begins … is it in the thought or in the

deed? If it is when you hand over money to Ashley Madison, that’s an awful lot

fewer that I might have expected. For anyone reading this thinking ‘there are

twice as many British accounts as Irish ones’ the sobering thought is that

there are huge differences in the relative populations of the two countries!

Just based on the latest figures for population for the Republic

and the UK

(I’m using the entire population as I couldn’t find any figures for the adult

segment alone) 0.004% of the UK have paid money to Ashley Madison, as opposed

to 0.0273% of the Irish population.

|

| UK & Ireland Revenue (C$) |

And just what has been paid? In the timescale

under review it appears that there were 25,590 transactions where money was

paid to Ashley Madison and this amounted to C$2,400,245.80. No matter how you

look at it, that’s a lot of money! This can be broken down as follows: C$2,151,348.91

from 23237 transactions in the UK and C$248,896.89 from 2353 Irish

transactions. The average spend per UK transaction was C$92.58, while it was

C$105.79 for their Irish counterparts.

Next question: Who’s getting paid? Well, Ashley

Madison, right? While everything, one presumes, eventually goes back to the

parent company, Avid Life Media, it goes via a variety of sub-companies as

recorded in the Account Name (Column B). There are four account names that are

variations on the name ‘ADL Media’ that brought in C$220,763.42 (C$198,343.73

from the UK and C$22,419.69 from Ireland). Avid Dating Life Inc brought in C$33,705.01

(C$2,327.69 from Ireland and C$31,377.31 from the UK). Two different accounts

associated with the name ‘AMDA’ (still probably not the American Musical and

Dramatic Academy) received C$39,877.00, all of it from the UK. There are twelve

separate account names based on ‘Ashley Madison’ that received C$1,864,889.24

from UK accounts and C$224,149.51 from Irish accounts (Total: C$2,089,038.75).

While I’m not at all clear on the specific services provided by each of these

corporate divisions, it’s pretty safe to assume that the ‘Ashley Madison’

account names relate to its core ‘have an affair’ business. We would appear to

be on firmer ground in assuming that CL Media refers to CougarLife. This

account name received two payments (both from the UK) totalling C$238. However,

both have associated error codes, indicating that the transactions were not

completed. EM Media (EstablishedMen?) did rather nicely, thank you very much,

taking in C$16,841.67 from 214 transactions from 150 unique accounts, all from

the UK. Poor old Swappernet brought in only C$19.95 from a single UK transaction

in 2013, which may go some way to explaining why it appears to have been shut

down.

|

| Account Names paid by UK & Irish members (Values in C$) |

Just to round out the preliminary examination of

the financial data, it is interesting to look at the cards used to pay for

Ashley Madison’s services. For both Ireland and the UK, the leading brands are,

in order, Visa (VI), MasterCard (MC), and (probably) American Express (AM).

|

| Credit Card brands used in valid transactions. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

Adding in the time dimension allows us to gain a

number of different insights. For example, looking only at the yearly revenues

shows a story of a company doing relatively well from 2008 to 2012, making a

marked improvement in 2013, but simply accelerating beyond expectations in 2014

and 2015 – even more so when one considers that the 2015 data only goes up to

June! Even when broken out into UK and Ireland data, a pretty similar story emerges for both.

However, breaking it down by financial quarter unveils a different narrative. Now

it’s clear that the major uptick in overall revenues only begins in Q4 of 2013.

While there is still a vast hike in revenue, it is clear that there was a major

hiccup in Q4 2014. There must have been a significant rethink of policy and direction

at that point, as the Q1 2015 figures were the best ever achieved. As all of

the Q2 2015 data is not available, there is a marked downturn in the latest

figures. In this instance, breaking it down again by country tells quite

different stories. The UK figures largely mirror the overall picture – natural

as they make up the lion’s share of the data. Like the parent data, there’s the

first major surge in in Q4 2014 and the Q4 2014 plunge. However, the UK data

shows a continued increase in the latest figures that is out of step with the

overall picture. This can be explained with reference to the Irish data where

Q2 2015 has shown an unprecedented slump. Other differences in the Irish data

include a much more marked increase in Q4 2013, followed by an immediate

collapse in the following quarter. Increasing the level of resolution to

monthly shows a much more fraught series of peaks and troughs of surging and

collapsing revenue streams. While the UK data shows a peak in revenues in April

2015, it seems that the Irish data climaxed in January 2015 and, despite

repeated attempts at revival (most notably in March and May 2015), was becoming

increasingly flaccid. This level of resolution can be increased to weekly, where

the data is reduced to staccato lunges, thrusts, and general throbbing. At this resolution, it is clear that the Irish market had been in serious decline for some time before the data breach. This

increase in resolution can be charted down to the minute and second, but the

data becomes remarkably difficult to visualise clearly, and my already-unravelling

ability to refrain from genital-based imagery goes into even steeper decline.

|

| Annual Revenues. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

|

| Annual Revenues by Quarter. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

|

| Annual Revenues by Month. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

|

| Annual Revenues by Week. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

If we remove the 2015 data (as it does not include

second half results) it is clear that across the years, business got better by

the quarter from slow starts in Q1 (Jan, Feb, & Mar) to the best results in

Q4 (Oct, Nov, & Dec). I’m not going to speculate on why that should be, but

both the UK and Irish data show the same results, if with slightly different

emphases. Again excluding the 2015 data, it appears that for the UK there was a

visible rise in expenditure (presumably correlated with a rise in actual

infidelity) in May, August, and September. Basically, as the year went on there

was an increase in payments made to Ashley Madison. The Irish, being different,

also show a general increase towards year end, but the peak month are July and

November … I’m not even going to try and explain why …

|

| Annual Revenues by Quarter. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

|

| Annual Revenues by Month. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

We’re on a roll! Looking at when in the month is

the most lucrative for Ashley Madison, we can clearly see that the UK picture (including

the 2015 data) shows peaks on the 2nd, 11th, 20th, 22nd, and 27th, though the

trend is towards falling revenue across the whole month. The Irish data, again

apparently loath to follow their neighbours, shows a series of small peaks of

similar size on the 2nd, 4th, 13th, 18th, and 21st before taking a

break in preparation for what can only be described as an earth-shattering

climax on the 29th. Overall, the trend is towards increased

financial activity across the month. There are even differences between the two

populations in terms of when the commit their greatest expenditures. The UK

data indicates a preference for Thursdays and Fridays, while the Irish data

shows distinct preferences for Wednesdays and Saturdays. Putting it all together, if you're from the UK, you're more likely to be spending money at Ashley Madison on Thursday August 11th, while Irish users are more likely to start laying out the cash on Saturday November 29th. The chronology of this

data is so fine that discussions can be formed at the second-level … this is

chronology like no archaeologist has ever dealt with before … and it’s

wonderful …

|

| Annual Revenues by Day of Month. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI (owing to a stupid labeling error, the chart says 'ex 2015' but does include 2015 data) |

|

| Annual Revenues by Day of Week. Top: overview. Bottom Left: UK. Bottom Right: RoI |

Perhaps less wonderful is the locational data. As

I said above, archaeologists are familiar with (usually) tightly controlled

locational data, be it at the site or context level. We’re not so good with the

idea that a site might have been in Scotland, but was actually in Killarney.

And that’s kinda’ what we’ve got here. I’ve used the Country and City fields to

attempt to map locations. The biggest issue here is that Ashley Madison, in

attempt to shield their members privacy, did not require email verification. They also

did not appear to enforce any form of robust location control or checking.

Thus, anyone wishing to hide their real world locations could do so without

problem. That is why there are a number of data entries that claim to be from

Ireland, but have, say, the city given as New York and include a New York

address. These I’ve attempted to weed out. Less easy to spot and eradicate are

instances where someone claimed to be in Ireland in the Country field and then

gave a valid Irish address that may not have been their own. There are

certainly plenty of real addresses in this data, but whether any of them are associated

with the people who live at those addresses is quite another matter. The other

issue is one of my own making and/or laziness … Tableau is good at spotting

real world places and generating mapable Latitudes and Longitudes for them …

but not perfect. Thus, there are over 3000 City codes that it has been unable

to place. With more time and patience that I possess, it would have been

possible to interrogate each one and manually add co-ordinates. Thus, the map

data is heavily skewed towards larger, more recognisable urban areas. There are

173 unique values in the City field for Ireland and another 819 for the UK. I’m

not going to discuss the UK data here, as I’m much less familiar with British

place names, however in the Irish data a number of things are visible. Firstly,

this field can be as specific as an individual Townland or it can be as

general as the County name. This is compounded by a number of Irish Counties

that have the same names as their major urban centres (e.g. Galway, Limerick, and Dublin). While I could have attempted to

augment the data with postcode and address-level indicators, I felt that it was

way too much trouble and potentially too revealing of where active Ashley

Madison account holders really were. While it’s deeply flawed and heavily

biased towards the larger urban centres, the data is still worth examining at

this level. The map (using only Settlement data) shows a clear preference for

the south-east of England, the Midlands, southern Wales, and the north-east,

along with the central belt of Scotland. In terms of the Island of Ireland,

there is a clear preference for Dublin, Meath, the east coast, and eastern

Ulster. If the marks are resized by the amount of expenditure (i.e. again Settlement data only), it is clear that

in Ireland. Dublin leads the way. In the UK there are notable ‘hot spots’ in

Glasgow, Middlesbrough, Salisbury, and Poole, but all are dwarfed by the

activities of London. As I say, this locational aspect of the data deserves

much more work and adjustment, but I’m content to leave this for further

students and researchers.

|

| All Tableau-mapable locations for UK & Ireland |

|

| All Tableau-mapable locations for UK & Ireland with marks re-sized to reflect relative expenditure |

The final aspect of the data I wanted to examine

here was at the individual-level. The first thing to say is that I’ll not be

revealing any names or exact real world locations. As many commentators have

noted, they may not refer to the actual people named. Even if they were

guaranteed accurately to identify everyone who spent money on this site, I find

little interest in naming and shaming any of them. Although there are multiple

issues with linking the cities, addresses, postcodes, and even the countries to

the names in the data set to real world people, I’ve found that they are

remarkably consistent across transactions. By this I mean that the details given

to make a payment in, say, July 2008 will be the same as when the member makes

a further payment the following month. We may not be able (or want to) identify

individuals, but the activities of individuals can be coherently tracked

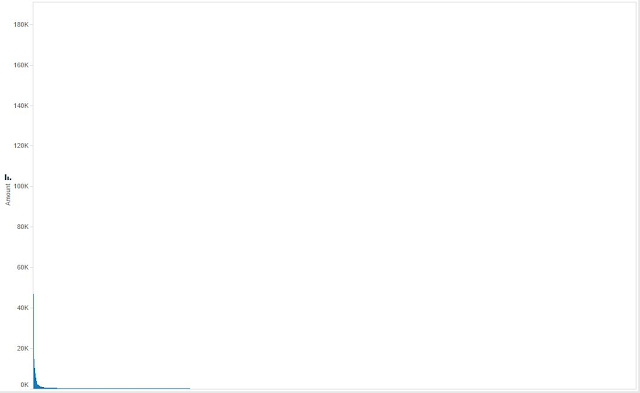

through the data. When you first graph this data (again, Settlements only) it

appears like there’s just a small smudge in the bottom left hand corner of the

page. It’s an issue with attempting to graph so many users against such a

variety of amounts of money. There are a few people who’ve paid an awful lot

and so many that have paid very little, they basically cancel each other out.

To be fair, things are not much better when you separate out the data by

country either. Instead it’s probably better to concentrate on a small number

of case studies within the data to examine generalities. The first thing to

note about looking at the respective top 20 accounts by amount spent is that

Ireland and the UK are vastly different. The top spending UK Account managed to

relieve himself of C$182,000. Admittedly, the top Irish account wasn’t terribly

far behind, spending C$119,300. But, while the UK accounts pretty much step

down along a gentle curve, the Irish ones simply drop between first and second

place – the next most generous Irish account spent C$7,502, as opposed to the

second place UK account that shelled out C$112,900. By the time you get to the

20th placed Irish account you’re talking about a spend of ‘only’ C$690. It’s

really not much when compared to the 20th placed UK account that forked over

C$10,870. For this top 20 group the averages are quite telling too. The UK

average here is C$40,933, while the Irish average is a ‘mere’ C$7,728. For the

entire dataset the average spend is C$255 – C$310 for Irish accounts and C$250

for UK ones. Not that I’m condoning it, but that sounds pretty reasonable for

an affair! I became intrigued by what some of the lower spending customers were

spending and I note that there are 1132 examples of people paying exactly C$19.

This is an important and much vaunted figure in that this was the price charged

by Ashley Madison for their ‘Full Delete’ service … that, it seems, they didn’t

actually carry out. With 275 examples from Ireland and the remaining 857 from

the UK, that’s C$21,508 that Ashley Madison got for (allegedly) doing very

little. When examined on an account, or individual level, it is clear that many

of these are the only payments ever made to Ashley Madison. These may be the

result of people desperately trying to erase a ‘prank’ account created by

co-workers, to people deciding that, now that they’ve had a bit of a look about

and a think about it, Ashley Madison and the services they offer are not for

them. Whatever about the latter group, I do sincerely hope that the former

group immediately followed this up by finding a job where they’re not

surrounded by asshats. Below this C$19 marker there are 9,009 transactions,

across 91 price points, where amounts were settled with Ashley Madison, ranging

from C$18.75 to C$8.08. All together, these totalled C$135,022.25 … an awful

lot of money to make in small transactions.

|

| All of the UK & Ireland account-level data by expenditure. So much data there's only a small smudge visible! |

I next wanted to look at how individual-level

accounts spent their money … basically, I wanted to see if they spent it all in

a short financial thrust or gently smouldered over a much longer timescale …

(Sorry! I had to take a break from typing as I started to hallucinate Barry White). Anyway, Mr

White successfully exorcised, I took a look at this for the UK and Ireland and

was rather confused by what I found. According to the data, our biggest spender

in the UK – lashing out a cool C$182K – did it in only two payments of C$91K in

August and September of 2014. But he’s not alone. The second placed account

paid out C$72,900 in March 2105, followed by two payments of C$20K each in the

two months following. Even in the eighth and ninth spots, they made their

entire spends over two transactions in a single month. I will admit that my first reaction was one of disbelief and shock - it seems implausible to me that so much money could be spent on a caprice over such a small span of time. I'm afraid that this aspect of life is beyond my experience (both the affairs and that amount of disposable cash), so I'm not able to comment on whether this is reasonable or plausible. For these apparent highest of high rollers, I did wonder if they were not the victims of fraud. This may yet prove to be the case, but there is no direct evidence of it that I can see in the data available. The Irish data is only

slightly less strange. The top payer managed to get through C$119,300 in 12

payments, varying between C$2,000 and C$12,800, in the period from November

2014 and March 2015. The third, fourth, and sixth ranked accounts all paid out

within a single calendar month (C$6,396, C$4,900, and C$1,120 respectively).

Only the second, eighth, and ninth ranked accounts paid their cash out in

smaller sums and over a relatively lengthy time frame. The second ranked account

shows Settlement activity in the period from April 4th 2011 to August 20th 2012.

The account holder spent C$7,866.99 over 105 transactions, with amounts ranging

from C$20 to C$249. As an aside, there is a person of the same name, same address,

but different account number, and different email (with a different credit card) that spent C$720 over 11

transactions in the period from July 3rd 2014 to April 4th 2014. Thus, it would

seem that individual accounts may not hold all the events of a single

individual. One way or another, this aspect of the data requires further

detailed study and scrutiny.

|

| Top 20 accounts by expenditure for UK (Left) and Ireland (Right) |

|

| Breakdown of expenditure by Top 10 UK accounts by month |

|

| Breakdown of expenditure by Top 10 Irish accounts by month |

This is as far as I’ve taken these analyses, but I

think that there’s much more there to be found and investigated. But beyond

these direct analyses, is there much that this form of data analysis can bring

to our understanding of modern British and Irish society? I think that the

answer has to be a resounding yes. This is exactly the type of data that

doesn’t make it into standard historical narratives precisely because it’s usually inaccessible and impossible to quantify. For this reason alone, I believe that

it is worthy of study and consideration. Certainly in terms of the Irish data

(north and south), it lends an important nuance to traditional, conservative

narratives about how ideas of ‘family’ and sexuality are understood and

presented. For the British data as much as the Irish, at its simplest level, it

gives the lie to so many standard stereotypes about the denizens of these

islands being sexually repressed and conservative. It was probably always thus,

the difference now is that the internet has provided the means to connect and

now we have the ability to analyse and interrogate the data. One way or another

– whatever the morality or legality of taking or using this data – it is here

and cannot be suppressed. Not only that, it will become more frequent and

increasingly normalised in the years to come. Here’s the challenge for

archaeologists, historians, and anyone interested in the current state of our

culture: how will we react to this data, how will we use it responsibly, and

what insights will we achieve?

Where do we go from here? In the first instance, I

think it’s important to note that I’ve only undertaken a small amount of

‘excavation’ on one small portion of this digital site – just the credit/debit

card data for the British and Irish members ... But there is so much more … not

just in terms of card transactions, but in the context of the data dump as a

whole. I do think that we need to move the analysis of this archive away from

the outing individual people to an atmosphere of genuine research at the

societal level. Think about it like undertaking a research dig on an ancient

city – there’s room for one team to investigate the houses of the wealthy,

while other projects look at the dwellings of the middle classes and the

workshops of the artisans. There’s still enough room for other groups again to

look at the aqueducts and the bathhouses … you just want to keep the treasure

hunters away from digging out the shiny stuff, shorn of all context. I think

that the archaeology metaphor holds when we consider that as large and

comprehensive as this data dump is, it is still just one ‘site’ (in both the

archaeological and internet senses). I hesitate to be seen to advocate for more

hacking of personal data, but should other related types of site become

available – for example, eHarmony, Tinder, Grindr, Christian Mingle, Match.com,

singlemuslim.com and any of the plethora of niche sites that are out there – we

may just be able to begin to create a landscape archaeology of the digital

realm. Should these be combined with data from other (non dating/hookup) digital sources, like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, MumsNet, Academia.edu and Instagram, then we could begin producing some genuinely deep and interesting insights at all levels from the individual to the planet as a whole ... and that, dear readers, is the true essence of archaeology and history!

Notes

For a project like this I’d normally direct the

reader to a Tableau presentation where they can play about with the data and

make their own discoveries and bring out the particular things that interest

them. I have not done that in this case, and for a number of reasons. In the

first place, I fell that despite my interest in it and argument that it is a

valid field for research, it is still too sensitive to release en masse – even if I did anonymise the

names and remove all even vaguely personal information. The second reason is

Tableau themselves. They do give off a very Geek-friendly vibe, but their heavy

handed response to users analysing portions of the WikiLeaks data and

uploading it to Tableau Public makes me think it’s better to be overly cautious

here (see also here

| here

| here

| here

| here).

Although Tableau have changed their policy in the time since (here

| here),

I’m not inclined to risk it. Instead, I just used Tableau Public to make the

visualisations and screen-grabbed them … it's not perfect, but it works!

I thought about writing to Visa and suggesting

that they attempt to capitalise on this data by taking out advertising to say:

‘Visa: Your card of choice for infidelities!’ ... but I have a feeling that

they’d not go for it. I even had a rough draft of a script for a TV advert … it

could have been great …

In doing research for this post, I stumbled upon the photography of Georgios Makkas and his 'Archaeology of Now' project looking at abandoned shopfronts in Greece. His work has a haunting quality that eloquently shows the effects of the recent economic downturn on the post-war Greek dream of family shop-ownership. See his work here and here

In doing research for this post, I stumbled upon the photography of Georgios Makkas and his 'Archaeology of Now' project looking at abandoned shopfronts in Greece. His work has a haunting quality that eloquently shows the effects of the recent economic downturn on the post-war Greek dream of family shop-ownership. See his work here and here

I just wanted to add that while the prevailing narrative

regarding the Ashley Madison data is one of heterosexual infidelities, there

are actually six categories of membership:

1: Attached Female SeekingMales

2: Attached Male Seeking Females

3: Single Male Seeking Attached Females

4: Single Female Seeking Attached Males

5: Attached Male Seeking Males

6: Attached Female Seeking Females

While the majority of coverage has centred on the

first two categories, this ignores a (probably) significant proportion of the

membership. In particular, the final two categories of individuals either in

heterosexual relationships seeking homosexual encounters or people in long-term

homosexual relationships, looking for affairs have been absent from the discussion.

I’ve not been able to find evidence in the credit card data to make differentiations at this level of detail, but I do think it’s worthy of study

and further research.

Comments

Post a Comment