Archaeology from the Interzone: Applications of the Burroughs-Gysin cut up method to problems in the Neolithic of Britain and Ireland

Regular readers of this blog will be familiar with my background as a field archaeologist. Many will also know of my attitude to archaeological theory: not so much 'ambivalent' as 'uncomfortable'. I started my university education a long time ago, when (at least in the west of Ireland) archaeological theory was not regularly considered and discussed, much less taught. In this, I am very much a product of my time and place. At one time (for a dare), I read Johnson's Archaeological Theory: An Introduction, but unfortunately found it quite impenetrable. I have, belatedly, attempted to get my head around the famous Transit Van excavation, by recreating my own version of it. The experience was equally intellectually exhilarating and challenging, as the process allowed me to break down some of my 'anti-theory' biases. This was coupled with a large number of thought-provoking comments on the blog, and in other social-media, which helped to confront my own ingrained thought processes. I would hardly say that I have come out the other side of this cerebral 'journey' as a whole-hearted convert to archaeological theory, but there is now an accommodation for all within my approach.

Just when I though I was 'becoming comfortable' with archaeological theory, I was asked by Stuart Rathbone to read an early draft of the paper you see below. Stuart is a field archaeologist of many years standing. He is co-author (with Victoria Ginn) of the rather wonderful book: Corrstown: A Coastal Community. Excavations of a Bronze Age village in Northern Ireland (reviewed here). He is also the central figure behind the Campaign For Sensible Archaeology, a clarion call for no-nonsense reporting and discussion in archaeology. In this paper, Stuart has stepped into a very different archaeological world: he advocates the use of the Burroughs-Gysin cut up technique as a method of gaining new and different insights into the archaeology of Neolithic Britain and Ireland. I will not pretend that this is an easy read - but it is rewarding. My initial fear was that it was a daft idea - definitely not 'sensible' - but his results are extraordinary. Whatever any reader thinks of the method, I feel that the results - these unlikely mergings and mashings of colliding sentences - brings forth something extraordinary: genuinely new insights into archaeology. For this reason, I am proud to introduce Stuart as the latest guest-blogger and honoured that he has chosen to share this wonderful, not-sensible, paper here.

[** If you like this post, please make a donation to

the IR&DD project using the button at the end. If you think the post is interesting or useful,

please re-share via Facebook, Google+, Twitter etc. **]

“Scientists, I hope, will become more creative and

writers more scientific” The Third Mind

William Seaward

Burroughs was one of the great outsider icons of 20th century

America, and his most famous novel, The Naked Lunch, is widely acknowledged as

a classic of mid 20th century experimental literature (Burroughs,

1959). His fiction is bizarre and difficult to read, graphic in the extreme and

was subject to obscenity prosecutions (Lotringer 2001, 51-2, 331-343). He also

wrote highly explicit works of auto biography which describe a life almost as

strange as his fiction. An unrepentant heroin user, unapologetic homosexual,

accidental wife killer, devotee of weird science, intercontinental bohemian,

gun nut and shotgun artist, his accounts of his life are always engaging and offer an easier read than much of his fiction

(Burroughs, 1953; 1985; 2001). In interview he was lucid and candid, often

extremely critical of contemporary politicians and demonstrated a formidable

range of interests (Lotringer 2001). Widely regarded as one of the key figures

of the ‘Beat Generation’ he was older than the other beat writers and in many

ways ploughed his own furrow. Indeed Burroughs himself constantly denied ever

being part of the ‘Beat Generation’ claiming repeatedly and somewhat

disingenuously that it was an American movement and that he was in

William Seaward

Burroughs was one of the great outsider icons of 20th century

America, and his most famous novel, The Naked Lunch, is widely acknowledged as

a classic of mid 20th century experimental literature (Burroughs,

1959). His fiction is bizarre and difficult to read, graphic in the extreme and

was subject to obscenity prosecutions (Lotringer 2001, 51-2, 331-343). He also

wrote highly explicit works of auto biography which describe a life almost as

strange as his fiction. An unrepentant heroin user, unapologetic homosexual,

accidental wife killer, devotee of weird science, intercontinental bohemian,

gun nut and shotgun artist, his accounts of his life are always engaging and offer an easier read than much of his fiction

(Burroughs, 1953; 1985; 2001). In interview he was lucid and candid, often

extremely critical of contemporary politicians and demonstrated a formidable

range of interests (Lotringer 2001). Widely regarded as one of the key figures

of the ‘Beat Generation’ he was older than the other beat writers and in many

ways ploughed his own furrow. Indeed Burroughs himself constantly denied ever

being part of the ‘Beat Generation’ claiming repeatedly and somewhat

disingenuously that it was an American movement and that he was in

The existence of

a ‘Beat Generation’ has been questioned by other participants in the movement

who highlight the small number of people involved. Gary Snyder claimed that “it

consisted of only three or four people, and four people don’t make up a generation”

(Charters 2001, XV). This view is rather restrictive but whilst those numbers

could probably be increased tenfold, the number of direct participants remains

extremely low. Covering the same theme Hettie Jones joked that “at one point

every one identified with it could fit into my living room, and I didn’t think

a whole generation could fit into my living room” (Charters 2001, 618).

Whatever the reality of the ‘Beat Generation’ it is clear that a series of

writers, most prominently William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Herbert

Hunkle and Gregory Corso, were part of

an extended social network and produced work exploring similar themes at

roughly the same time. These shared themes include drug use, sexual

relationships, mental illness, the nature of art, the nature of spirituality

and the relationship of the individual to the divine. Burroughs’ work stands

somewhat apart in its focus on prose over poetry, the graphic and lurid

descriptions of sex and drug taking, and the use of the infamous ‘cut up’

technique.

Throughout

Burroughs’ work there are repeating themes, some of which relate to topics that

may be of interest to the archaeologist. At an early point Burroughs had taken

a formal interest in the subject; after completing a degree in English

Literature at Harvard in 1936 he undertook some post graduate studies in

anthropology and archaeology (Lotringer 2001, 48). Historical and pseudo

historical figures feature as characters in his fiction and are discussed,

manipulated and misrepresented in his nonfiction. Without doubt the two most

important historical characters in Burroughs’ work are Hassan i Sabbah, the

leader of the Arabian Hashshashin sect in 11th century Iran, and

Captain Mission, the alleged leader of a pirate utopia in Madagascar during the

17th century, but who is widely regarded as a literary invention of

Daniel Defoe (Burroughs 1981). Locations are often drawn from historical

sources or drawn from his travels around the Americas ,

Europe and Africa . Occasionally his work verges

into ethnographical territories, although with a clear focus on acquiring and taking

drugs and the workings of the local homosexual scene (Burroughs & Ginsberg

1963). Time in Burroughs’ work is fluid and often non-linear; journeys can be

made forwards and backwards in time either through design or accident.

Different methods are used by his characters for temporal relocation, but they

never utilise the large machinery of science fiction. Typically time travel

occurs at death, during sexual climax, during drug induced trances, through the

use of the ‘cut up’ technique, or through a combination of any of the above.

The Burroughs-Gysin

cut up technique was first conceived by Burroughs’ friend and collaborator Brion

Gysin whilst the pair were living in the ‘Beat Hotel’ in Paris in 1957 (Lotringer

2001, 66-7; Wilson & Gysin 2000, 63). Gysin having accidently cut up some

newspapers with a scalpel recombined the cut up texts to make new ones. After

showing the method to Burroughs they experimented with it for some time before

co authoring two of the first cut up publications, ‘The Third Mind’ (the title

referring to the third presence that had been unconsciously released by the two

collaborators during the cut ups) and ‘The Exterminator’ (Burroughs & Gysin

1960; Sobieszek 1996, 55-73). Gysin also contributed to ‘Minutes to Go’, a

collaborative effort that included pieces by Gregory Corso and Beiles Sinclair

(Burroughs et al 1960). Subsequently

Gysin abandoned the technique claiming that the results were “absolutely

unreadable, nobody could read them, you just – William himself said he couldn’t

read them a second time...uh, they produced a certain kind of very unhappy

psychic effect...” (Willson & Gysin 2000, 62). Burroughs continued to

experiment with the technique, and the related ‘fold in’ method, for a

considerable period of time publishing several books of largely cut up text

that had been re-edited into some semblance of order, ‘The Soft Machine’, ‘The

Ticket that Exploded’ and ‘Nova Express’ (Burroughs 1961; 1962; 1964). Subsequently

he continued using the ideas generated through cutting up texts to inspire

slightly more conventional works, in particular in the ‘Wild Boys’ and ‘Western Lands Island 1993).

Burroughs frequently

refers to the use of the cut up technique within his fiction, and it is one

method through which his characters can affect temporal translocation. The

clearest example of this is found in the routine, ‘The Mayan Caper’, first

published as part of ‘The Soft Machine’ collection. In this work the

protagonist first uses cut up techniques to travel back to the height of the

Mayan civilisation and, once he arrives, uses cut up techniques to reverse the

mind control machines that the priestly cast are using to subjugate the

population and instigates a revolution (Burroughs 1961). This routine clearly

reflects Burroughs firmly held belief that the cut up techniques were

inherently powerful and could be used to influence genuine change in the real

world (Lotringer 2001, 155; Robinson 2007, 6-8).

Applying the Burroughs-Gysin cut up technique to

problems in British prehistory

The worlds of literature

and archaeology have occasionally collided. Typically this has been where

accounts of monuments or excavations are included within works of fiction and

have subsequently been mined for information relevant to archaeologists as any

other historical source might be assessed. Following a more traditional

literary analysis method a recent study has looked at the influence of

archaeology in the works of Thomas Hardy (Davies 2011). A series of papers

published by Bournemouth University following a TAG session examine the role of

archaeology and its practitioners in Science Fiction books and TV shows, and

even explores imaginary archaeologies that exist in fictional settings such as

Terry Pratchett’s ‘Discworld’ (Russell 2002; Brooks 2002; Brown 2002; Boyd

2002). A more recent paper has examined the various references to archaeology

in the TV show ‘Futurama’, and the way in which archaeology is repeatedly used

as a source of complex metaphors by the script writers (Hall 2011). Whilst this

may establish some form of precedent for the following study, it has to be

acknowledged that the nature of Burroughs’ methods means the idea that anything

useful generated by its application would obviously need to be treated with

great caution. In defence of this I can only offer the old platitude that

fortune is supposed to favour the brave...

A long standing

problem for archaeologists attempting to understand the Neolithic period is the

separation of religious and more practical aspects of life that is locked into

the modern mindset. It has been convincingly argued that this sort of

separation may not have been part of the Neolithic world view and that all

aspects of life may have been infused with symbolic and religious meaning (Topping

1996, 163-70). Despite this acknowledgement the problem of describing a more

cohesive world view seems to constantly challenge archaeological writers. For

example critical studies of houses from the Neolithic have often sought to

emphasise ritual aspects of the building and have subsequently interpreted

building foot prints in various non domestic ways, such as cult houses, feasting

halls, seasonal meeting places, mortuary houses and comparisons have even been

drawn with the cursus monuments (Barclay 1996, 73-5; Cross 2003; Loveday 2006;

Pryor 2003, 139-46). Unfortunately it seems that whilst superficially

acknowledging the way which domestic activities may not be separated from

religious and symbolic ones, these explanations tend to move interpretations

fully into the religious realm and properly unified explanations have remained

elusive.

The Burroughs-Gysin

cut up method represents an admittedly avant-garde method through which such a

unified understanding could potentially be achieved. By taking various texts

dealing with different aspects of the Neolithic period and subjecting them to

cut up style manipulation it may be possible to generate ideas and explanations

that are not directed by our modern preconceptions. Ideas generated by ‘the

third mind’ are not created through rational argument but through random

associations in an automated and undirected way. Whilst the resulting cut ups

would inevitably be unpalatable to the reader, it is suggested that useful

concepts might be generated that could be used as the starting points for new

discussions that would not be so directly derived from modern viewpoints.

Burroughs’

himself was clearly fascinated by the actual process of physically cutting up

pages of text, and imported great symbolism and mysticism to this destructive

process. However Burroughs’ was ever drawn to pseudo science and occultism. He

spent considerable lengths of time inside one of Wilhelm Reich’s Orgon

Accumulators and seemed convinced, for a while at least, that he had met an

Artificial Intelligence in London

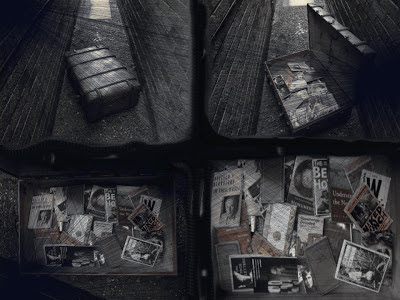

The method used

here was simply to copy sections of text into a Microsoft Word file and mix

them up using the copy and paste functions. The font colour of text belonging

to different sources was changed so that during the mixing process the origin

of any text could be identified and the degree of rearrangement that had been

achieved could be tracked (Figure 1). The included texts were sourced simply

from whatever material relating to the Neolithic had been accumulated on a

portable hard drive that was conveniently to hand. Passages were selected from

pieces discussing a wide variety of topics including houses, enclosures,

settlement patterns, warfare, burial, territory, drug use, art and so on

(Sources listed in Appendix) that seemed to cover a wide range of aspects of

Neolithic life. Passages included several pieces I had written or contributed

to, several pieces I was very familiar with and had read on different

occasions, and several pieces that I was still trying to find the time to read

for the first time. The selections were exclusively made from discursive

sections, and were skimmed over to check for relevance but not read in depth.

The cut up process thus began during this initial phase and segments were

somewhat rudely snatched out of larger passages, rather than being included in

their entirety. Academic debris (References, figure numbers etc) were removed

from the text prior to the commencement of the cuts, as were all of the

original paragraph breaks.

Once the

selected texts had been assembled and assigned colours they were subject to six

separate ‘cuts’ or passes, each one being saved as a separate file. Figure 1

illustrates the degree of rearrangement achieved at the end of the 2nd,

4th and 6th cuts respectively. A seventh cut was

attempted but by that point all sentence structure had totally broken down and

the result was mostly a long string of unconnected words and phrase fragments,

and this final cut was discarded. Reading through the different cuts

interesting phrases were identified and saved individually. The most useful of

these are presented below, with minor alterations to make them scan more easily

to the reader; where it has been necessary to add in additional words to enable

the text to be read the addition is shown in italics. The original source of

each section of the cut up is indicated by a numerical superscript tied into

the list in the appendix. Each selection is followed by a brief examination of

the interesting points that occurred to the author as the text was encountered.

No attempt has been made to create a larger narrative from these cut ups, they

are simply offered as interesting places to begin further discussions.

Figure 1. Changing the font colour of text from different sources provided a

simple method to monitor the level of destruction wrought upon the original sent ence

structure.

Results

The First Pass

1)

It has been suggested that the

house at Ballyglass, Co. Mayo, was deliberately demolished in order to

construct the overlying court tomb. Cooney lists an array of possible reasons

why such houses¹ use substances and techniques to alter perception and

consciousness; a neglected aspect of past cultures².

This cut up highlights

how the use of narcotic substances and decorative techniques may have meant

that being inside a Neolithic long house could have been a far more vibrant

experience than is reflected by the foundation slots and post holes that are

encountered during archaeological excavation. Such ideas are familiar from the

archaeological literature however, and often revolving around ethnographic

parallels (eg Richards 1996; Hugh Jones 1996). If such an enhanced experience

was taking place within the building it might have a relevance to why the court

tomb was subsequently constructed over its remains. Again the presence of house

found underneath tombs has been the subject of a great deal of discussion, and

this cut up brings no new insights, it has been included here as it marked an

early indication that the cutting process might actually create useable results

(Grogan 1996, 57; Jones 2007, 136-7).

The Second Pass

2)

clearfires³

⁴ before the cairn or chambers were built⁴.

The term

‘clearfires’ is a very interesting one, as it suggests a particular type of

fire that we do not presently have a specific word for. As an example of what

we could term a ‘clearfire’ might be the burning of mortuary houses prior to

the construction of long barrows, as had apparently happened at Raisthorpe,

Street House Farm and Kemp Howe all in

Yorkshire, Lochill, Dumfies and Galloway and Dalladies, Grampian for example (Russell

2002, 59-60; Piggott 1972, 34-5; Vyner 1984, 185-191). The term ‘clearfire’ also

suggests we should be looking for other specific types of fire, and

investigating the way in which fire was used, and controlled for different

purposes. For instance, a ‘dayfire’ could be seen as a quick and well

controlled burn, quite different to the ‘clearfire’ which might be large and

rage uncontrolled, or a ‘slowfire’ which may have been a long duration burn. This

cut up highlights that there may be many different types of fire and that

during excavation we should attempt to identify them more precisely. Magnetic

readings of burnt soils can inform us about the temperatures achieved and

duration of burns, but these are not presently undertaken routinely (James

Bonsall pers comms). Combined with full species identification of charred

remains it might be possible to identify more accurately the different types of

burning we encounter.

3)

Its outer

wall was⁵ for communication

between disparate groups. As discussed, the tor enclosure evidence fits well

into the lives of a society that continued a fairly mobile existence; indeed,

the enclosure of specific tors at certain places in the landscape would seem to

argue more strongly for a reference to⁶ occupants of

the area¹.

This cut up seems to reinforce the idea that walls and boundaries

were more than simple, functional, divisions of space and may have had

particular meanings that were being communicated to particular groups and

possibly to denote limits of access for cultural rather than functional or

economic reasons.

The Third

Pass

4)

The decline of the Neolithic

settlement at this site may have been due to a number of factors¹; art was

apparently derived from endogenous visions associated with some form of

mind-altering practice²

This cut up suggests a link between art and settlement patterns that

would not normally be found in our discussions. Could changes in art really

influence settlement patterns? Changes in art styles, such as the development

of Groovedware, are observed to occur concurrently with larger shifts in

culture, but could the changes in art, especially if connected to narcotic

practices, be seen as a cause rather than an effect of cultural change?

5)

conflict ensued with the formation of a quasi-political

unity⁶, “The serpentine beads¹”. This

may have involved the use of hallucinogenic substances²

This cut up suggests the presence of a social group named after a

specific artefact type, certainly a possibility, but ethnonyms are a difficult

subject that probably can’t be explored with much purpose during this period.

More interestingly it links the use of hallucinogenic substances to the

formation of political groups and to the development of conflict, possibly even

warfare. A convincing argument has been made that the style of megalithic art

found in Ireland and western Britain can be attributed to the use of strong

hallucinogens, however we might usefully examine how the use of such substances

effect other aspects of the societies we study (Dronfield 1995; Lewis-Williams

& Pearce 2005, 39-59).

6)

data from² Quartz

seems to have been important to the Neolithic people⁴

This

simple cut up highlights the importance that some Neolithic people placed on

quartz, which is often found in different guises at burial sites and other

locations. For example huge numbers of rounded quartz pebbles were brought to

the Neolithic enclosures at Billown on the Isle of Man ,

whilst quartz crystal rods have been recovered from several court tombs, such

as Annaghmare

Court Cairn, Co

Armagh and Creevykeel Court Cairn, Co Sligo, and quartz

pavements were constructed around the exterior of the Boyne Valley

The Fourth

Pass

7)

This may have involved the use of hallucinogenic

substances or² early Neolithic agriculture⁷

Again this cut up emphasises the role of hallucinogens in Neolithic

society. Here the cut up presents hallucinogens as an explanation that is equal

in weight to Early Neolithic agriculture. This triggers the amusing, but not

perhaps useful notion, that the motivation behind the Neolithic colonisation of

Britain and Ireland Britain

and Ireland

8)

the house¹ chamber³

This simple cut up immediately brings to mind the shared

architectural features seen between the houses at Barnhouse and the Maes Howe

passage tomb on Orkney. The term ‘house chamber’ and the obvious juxtaposition,

‘chamber house’ could be useful terms to discuss the relationship between

domestic and megalithic architectural traditions. However it should be

emphasised that this relationship has been identified long ago by more

traditional and logical methods and has already been discussed at length by

Richards, amongst others (Richards 1993; Garrow et al 2005).

The Fifth

Pass

9)

amongst the fragmentary remains of⁸ reoccurring

assemblage³

This final cut up has a seemingly innocuous meaning, but was

selected originally for its rather pleasingly ‘beat’ rhythm. However on

reflection it may be pointing to a useful idea concerning the way in which we

interpret artefacts assemblages, specifically regarding the point at which

fragmentation occurred. Whilst we often think of finds assemblages as being

incomplete due to all manner of post deposition processes, in many instances

these assemblages may never have been complete. The author has recently

discussed the meaning of small fragmentary assemblages found in isolated prehistoric

pits, but fragmentation in other contexts, such as areas outside of tombs for

example, or in areas around settlements, could be usefully explored (Rathbone

2012). Contemporary activities may have been taken place amongst, and actively

involving, fragmentary assemblages. The sorts of complex spreads of different

materials found in the court and chambers of tombs such as Rathlackan, Co Mayo,

may be interpreted as assemblages that have become disturbed over time (Byrne et al 2009). However another reading of

the same evidence would be that the instead we should think of these areas as

more akin to middens, with ceremonies taking place amongst the debris left

behind by previous events, and ever more material accumulating over time. In

this scenario assemblages would not be seen as disturbed and incomplete, they would

be interpreted as never having been complete or well ordered in the first

place.

Conclusions

The above

discussions are offered as points which could be expanded on in more depth

elsewhere. Rather than being presented as evidence of the cut up technique

producing new insights, they are simply offered as what Burroughs might refer

to as ‘Ports of Entry’, starting places for new discussions. Certainly the cut

ups present several examples where the normal order of cause and affect appear

interestingly reversed, and there are several examples of places where intriguing

links are made between processes which would normally not be strongly

associated with each other. However how much any of this really results from

the actions of ‘the third mind’ rather than simply reflecting some of my own

long term concerns, in particular the general absence of sensible discussion

about the role of drug taking in Neolithic Society, the lack of a holistic

understanding of Neolithic society and the overemphasis on ritual behaviour, is

not entirely clear. In effect random occurrences in the cut ups may have

reminded me of ideas I already held, although I do not think that such a process

would account for all of the points of interest that were identified. As

Burroughs himself put it, “What appears to be random my not, in fact, be random

at all. You have selected what you want to cut up. After that, you select what

you want to use” (Lotringer 2001, 262).

Two concepts were

generated by the cut ups that I feel could be genuinely interesting to explore

in greater detail. The first is the idea of examining different types of

burning events during the Neolithic, although the technical aspects of such a

study are beyond my own rather limited range of skills. The second is the

notion of events taking place amongst unsorted and already fragmented spreads

of artefacts, and this is something that I may explore in the future,

specifically in regard to the activities taking place in and around Irish Court

Tombs, but perhaps also looking at examples of ‘structured depositions’ found

in house foundations and enclosure ditches. The results of the excavations that

took place at the intertidal site, The Stumble, in Kent may be particularly

important in this regard as that excavation suggests that the sheer quantity of

broken and unsorted material that would be present around areas of Neolithic

activity may have been grossly underestimated (Brown 1997).

This attempt to

use the Burroughs-Gysin method has therefore been an amusing, and not entirely

unsuccessful experiment. It would seem extremely unlikely that such a technique

would find much favour in the archaeological community, and it is far from

certain that any discussions subsequently presented that had their ultimate

origin in a cut up text would be well received. This is not necessarily a bad

thing. The current post-modernist paradigm in British archaeology is not one I

am particularly at ease with, and it is only from that sort of theoretical

‘anything goes stance’ that this sort of technique could be reasonably

justified (Rathbone 2010). Personally I typically favour a far more traditional

and evidence based approach to archaeology, and this sort of exercise lies well

outside of my academic comfort zone. The words of the art critic Terence Kealey

ring a resounding note of caution, “We live with the post-modern insights by

ignoring them in practice whilst acknowledging them in theory” (Quoted in

Flemming 2006). Ultimately perhaps a more fitting place for such a discussion

would be in a literary study relating to the work and influence of Burroughs

rather than in an archaeological publication. Having said that time will tell

if this experiment does lead to further publications and that may be a better

measure of the success, or otherwise, of this experiment.

References

Barclay, G.J. 1996 Neolithic houses in Scotland. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic Houses in Northwest Europe and Beyond, 61–76. Oxford: Oxbow.

Boyd, B. 2002 “The myth makers”: archaeology in Doctor Who. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 30-37. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Brooks, A. 2002 “Under old earth”: material culture, identity and history in the work of Cordwainer Smith. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 77-84. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Brown, N. 1996 A landscape of two halves: The Neolithic of the Chelmer Valley/Blackwater Estuary, Essex. In P. Topping (ed) Neolithic Landscape, 87-98. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Brown, M. 2002 Imaginary places, real monuments: field monuments of Lancre, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 67-76. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Burroughs, W.S. 1953 Junkie: Confessions of an unredeemed drug addict. New York: Ace Books.

Burroughs, W.S. 1959 The naked lunch. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1961 The soft machine. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1962 The ticket that exploded. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1964 Nova express. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1971 The wild boys. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1973 Exterminator! New York: Viking Press.

Burroughs, W.S 1980 Port of saints. Berkeley: Blue Wind Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1981 The cities of the red night. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Burroughs, W.S. 1984 The place of dead roads. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Burroughs, W.S. 1985 Queer. New York: Viking Press.

Boyd, B. 2002 “The myth makers”: archaeology in Doctor Who. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 30-37. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Brooks, A. 2002 “Under old earth”: material culture, identity and history in the work of Cordwainer Smith. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 77-84. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Brown, N. 1996 A landscape of two halves: The Neolithic of the Chelmer Valley/Blackwater Estuary, Essex. In P. Topping (ed) Neolithic Landscape, 87-98. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Brown, M. 2002 Imaginary places, real monuments: field monuments of Lancre, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction, 67-76. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Burroughs, W.S. 1953 Junkie: Confessions of an unredeemed drug addict. New York: Ace Books.

Burroughs, W.S. 1959 The naked lunch. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1961 The soft machine. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1962 The ticket that exploded. Paris: Olympia Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1964 Nova express. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1971 The wild boys. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1973 Exterminator! New York: Viking Press.

Burroughs, W.S 1980 Port of saints. Berkeley: Blue Wind Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1981 The cities of the red night. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Burroughs, W.S. 1984 The place of dead roads. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Burroughs, W.S. 1985 Queer. New York: Viking Press.

Burroughs, W.S. 1986 Break through in Grey Room (LP). Sub Rosa (CD 006-8).

Burroughs, W.S. 1987 The western lands. New York: Viking Penguin.

Burroughs, W.S. 2000 Last words: The final journals of William S. Burroughs. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S., Corso, G., Gysin, B., & Sinclair, B. 1960 Minutes to go. Paris: Two Cities Edition.

Burroughs, W.S. & The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprosy 1993 Spare Ass Annie and other tales (LP). Island (422-162-535-003-2).

Burroughs, W.S. & Ginsberg, A. 1963 The Yage letters. San Francisco: City Lights.

Burroughs, W.S. & Gysin, B. 1960 The exterminator. San Francisco: The Auherhahn Press.

Byrne, G., Warren, G., Rathbone, S. McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological excavations at Rathlackan (E580) stratigraphic report. Dublin: Heritage Council.

Charters, A. 2001 Beat down to your soul. London: Penguin.

Cross, S. 2003 Irish Neolithic settlement architecture – a reappraisal. In A. Armit, E. Murphy, E. Nelis, & D. Simpson (eds), Neolithic settlement in Ireland and Western Britain, 47-55. Oxford: Oxbow.

Davies, M.J.P. 2011 A distant prospect of Wessex: Archaeology and the past in the life and works of Thomas Hardy. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Darvil, T. 2003 Billown and the Neolithic of the Isle of Man. In A. Armit, E. Murphy, E. Nelis, & D. Simpson (eds), Neolithic settlement in Ireland and western Britain, 112-119. Oxford: Oxbow.

Dronfield, J. 1995. Subjective visions and the source of Irish megalithic art. Antiquity 69, 539–549.

Flemming, A. 2006 Post-processual landscape archaeology; a critique. Cambridge Archaeology Journal 16:3, 267-280.

Garrow, D., Raven, J. & Richards, C. 2005 The Anatomy of a megalithic landscape. In C. Richards (ed.), Dwelling among the monuments: the Neolithic village of Barnhouse, Maeshowe Passage Grave and surrounding monuments at Stenness, Orkney, 249-259. Oxford: Oxbow.

Gogan, E. 1996. ‘Neolithic house in Ireland’, in T. Darvil & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 41–60. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Hall, M.A. 2011 Matt Groening and David X. Cohen (creators), Futurama (USA TV series and DVD films, 1999–2009) European Journal of Archaeology 14: 1, 274-6.

Hugh-Jones, C. 1996 Houses in the Neolithic imagination: An Amazonian example. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 185–194. Oxford: Oxbow.

Jones, C. 2007 Temples of stone: Exploring the megalithic tombs of Ireland. Cork: The Collins Press.

Kerouac, J. 1957 On the road. New York: Viking Press.

Lewis-Williams, D. & Pearce, D. 2005 Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, cosmos and the realm of the gods. London: Thames & Hudson.

Lotringer, S. 2001 Burroughs Live: The collected interviews of William S Burroughs 1960-97. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Miles, B. 2000 The Beat Hotel: Ginsberg, Burroughs & Corso in Paris 1957 – 1963. London: Atlantic Books.

Piggott, S. 1972 Excavation of the Dalladies long barrow, Fettercairn, Kincardineshire. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 104, 23-47.

Pryor, F. 2003 Britain BC: Life in Britain before the Romans. London, Harper Perennial.

Pollard, T., Banks, I., Bordman, S., Carter, S., Jones, A. & McKinley, JI. 1997 Excavation of a Neolithic settlement and ritual complex at Beckton Farm, Lockerbie, Dumfries & Galloway. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 127 (1997), 69-121.

Rathbone, S. 2010 Sensible archaeology? Past horizons; Opinions

http://www.pasthorizons.com/index.php/archives/10/2010/sensible-archaeology

Rathbone , S. 2012 Archaeology at the end of the road. Seanda, 7, 48-51.

Richards, C. 1993 Monumental choreography: Architectural and spatial representation in Late Neolithic Orkney. In C. Tilley (ed) Interpretive archaeology, 143-78. London: Berg.

Richards, C. 1996 Life is not that simple: Architecture and cosmology in the Balinese house. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 171–185. Oxford: Oxbow.

Robinson, E.S. 2007 Taking the Power Back: William S. Burroughs’ use of the cut-up as a means of challenging social orders and power structures. Quest, 4. http://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/QUEST/FileStore/Issue4PerspectiviesonPowerPapers/Filetoupload,71743,en.pdf

Robinson, E.S. 2011 Shift Linguals: Cut up narratives from William S Burroughs to the present. Post-modern Studies 46. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi B.V.

Russell, L. 2002 Archaeology and Star trek: Exploring the past in the future. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 19-29.

Russell, M. 2002 Monuments of the British Neolithic: The roots of architecture. Stroud: Tempus.

Sobieszek, R.A. 1996 Ports of entry: William S Burroughs and the arts. London: Thames & Hudson.

Stout, G. 2002 Newgrange and the Bend in the Boyne. Cork: Cork University Press.

Topping, P. 1996 Structure and ritual in the Neolithic house: Some examples from Britain and Ireland. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 157–170. Oxford: Oxbow.

Vyner, B.E. 1984 The excavation of a Neolithic cairn at Street House, Loftus, Cleveland. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 50, 151-195.

Waterman, D.M. 1965 The court cairn at Annaghmare, Co Armagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 28, 3-46.

Wilson, T. & Gysin, B. 2001 Here to go. Clerkenwell: Creation Books.

Appendix

Sources for cut ups

1) Purcell, A. 2002 Excavation of three Neolithic houses at Corbally, kilcullen, Co. Kildare. The Journal of Irish Archaeology, X1

2) Dronfield, J. 1995. Subjective Visions and the Source of Irish Megalithic Art. Antiquity 69, 539–549

3) Byrne, G., Warren, G., Rathbone, S. McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological Excavations at Rathlackan (E580) Stratigraphic Report. Heritage Council. http://www.heritagecouncil.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/INSTAR_Database/Neolithic_and_Bronze_Age_Landscapes_of_North_Mayo_Progress_Reports_6.pdf

4) Marshall, D.N. and Taylor, I.D. 1976 The excavation of the chambered cairn at Glenvoidean, Isle of Bute. Proceedings of the society of Scottish Antiquaries, 1976-7, 1-39

5) Parker Pearson, M.; Pollard, J.; Richards, C.; Thomas, J.; & Tilley, C. 2006 The Stonehenge River Side Project 2006 Interim Report

http://www.shef.ac.uk/content/1/c6/02/21/27/summary-interim-report-2006.pdf

6) Davies, S. R 2010 The Early Neolithic Tor Enclosures of Southwest Britain. PHD Thesis Birmingham University

http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/1141/1/Davies_S_10_PhD.pdf

7) Caulfield, S., Warren, G., Rathbone, S., McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological Excavations at the Glenulra Enclosure (E24) Stratigraphic Report

http://www.heritagecouncil.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/INSTAR_Database/Neolithic_and_Bronze_Age_Landscapes_of_North_Mayo_Progress_Reports_4.pdf

8) Johnston, P. & Tierney, J. 2011 Ballinglanna North 3, Co. Cork: Two Neolithic Structures and Two Fulachta Fiadh. Eachtra Journal 10

http://eachtra.ie/index.php/journal/e2416-ballinglanna-north3-co-cork/

Burroughs, W.S. 1987 The western lands. New York: Viking Penguin.

Burroughs, W.S. 2000 Last words: The final journals of William S. Burroughs. New York: Grove Press.

Burroughs, W.S., Corso, G., Gysin, B., & Sinclair, B. 1960 Minutes to go. Paris: Two Cities Edition.

Burroughs, W.S. & The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprosy 1993 Spare Ass Annie and other tales (LP). Island (422-162-535-003-2).

Burroughs, W.S. & Ginsberg, A. 1963 The Yage letters. San Francisco: City Lights.

Burroughs, W.S. & Gysin, B. 1960 The exterminator. San Francisco: The Auherhahn Press.

Byrne, G., Warren, G., Rathbone, S. McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological excavations at Rathlackan (E580) stratigraphic report. Dublin: Heritage Council.

Charters, A. 2001 Beat down to your soul. London: Penguin.

Cross, S. 2003 Irish Neolithic settlement architecture – a reappraisal. In A. Armit, E. Murphy, E. Nelis, & D. Simpson (eds), Neolithic settlement in Ireland and Western Britain, 47-55. Oxford: Oxbow.

Davies, M.J.P. 2011 A distant prospect of Wessex: Archaeology and the past in the life and works of Thomas Hardy. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Darvil, T. 2003 Billown and the Neolithic of the Isle of Man. In A. Armit, E. Murphy, E. Nelis, & D. Simpson (eds), Neolithic settlement in Ireland and western Britain, 112-119. Oxford: Oxbow.

Dronfield, J. 1995. Subjective visions and the source of Irish megalithic art. Antiquity 69, 539–549.

Flemming, A. 2006 Post-processual landscape archaeology; a critique. Cambridge Archaeology Journal 16:3, 267-280.

Garrow, D., Raven, J. & Richards, C. 2005 The Anatomy of a megalithic landscape. In C. Richards (ed.), Dwelling among the monuments: the Neolithic village of Barnhouse, Maeshowe Passage Grave and surrounding monuments at Stenness, Orkney, 249-259. Oxford: Oxbow.

Gogan, E. 1996. ‘Neolithic house in Ireland’, in T. Darvil & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 41–60. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Hall, M.A. 2011 Matt Groening and David X. Cohen (creators), Futurama (USA TV series and DVD films, 1999–2009) European Journal of Archaeology 14: 1, 274-6.

Hugh-Jones, C. 1996 Houses in the Neolithic imagination: An Amazonian example. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 185–194. Oxford: Oxbow.

Jones, C. 2007 Temples of stone: Exploring the megalithic tombs of Ireland. Cork: The Collins Press.

Kerouac, J. 1957 On the road. New York: Viking Press.

Lewis-Williams, D. & Pearce, D. 2005 Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, cosmos and the realm of the gods. London: Thames & Hudson.

Lotringer, S. 2001 Burroughs Live: The collected interviews of William S Burroughs 1960-97. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Miles, B. 2000 The Beat Hotel: Ginsberg, Burroughs & Corso in Paris 1957 – 1963. London: Atlantic Books.

Piggott, S. 1972 Excavation of the Dalladies long barrow, Fettercairn, Kincardineshire. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 104, 23-47.

Pryor, F. 2003 Britain BC: Life in Britain before the Romans. London, Harper Perennial.

Pollard, T., Banks, I., Bordman, S., Carter, S., Jones, A. & McKinley, JI. 1997 Excavation of a Neolithic settlement and ritual complex at Beckton Farm, Lockerbie, Dumfries & Galloway. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 127 (1997), 69-121.

Rathbone, S. 2010 Sensible archaeology? Past horizons; Opinions

http://www.pasthorizons.com/index.php/archives/10/2010/sensible-archaeology

Rathbone , S. 2012 Archaeology at the end of the road. Seanda, 7, 48-51.

Richards, C. 1993 Monumental choreography: Architectural and spatial representation in Late Neolithic Orkney. In C. Tilley (ed) Interpretive archaeology, 143-78. London: Berg.

Richards, C. 1996 Life is not that simple: Architecture and cosmology in the Balinese house. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 171–185. Oxford: Oxbow.

Robinson, E.S. 2007 Taking the Power Back: William S. Burroughs’ use of the cut-up as a means of challenging social orders and power structures. Quest, 4. http://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/QUEST/FileStore/Issue4PerspectiviesonPowerPapers/Filetoupload,71743,en.pdf

Robinson, E.S. 2011 Shift Linguals: Cut up narratives from William S Burroughs to the present. Post-modern Studies 46. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi B.V.

Russell, L. 2002 Archaeology and Star trek: Exploring the past in the future. In M. Russell (ed) Digging holes in popular culture: Archaeology and Science Fiction. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 19-29.

Russell, M. 2002 Monuments of the British Neolithic: The roots of architecture. Stroud: Tempus.

Sobieszek, R.A. 1996 Ports of entry: William S Burroughs and the arts. London: Thames & Hudson.

Stout, G. 2002 Newgrange and the Bend in the Boyne. Cork: Cork University Press.

Topping, P. 1996 Structure and ritual in the Neolithic house: Some examples from Britain and Ireland. In T. Darvill & J. Thomas (eds), Neolithic houses in northwest Europe and beyond, 157–170. Oxford: Oxbow.

Vyner, B.E. 1984 The excavation of a Neolithic cairn at Street House, Loftus, Cleveland. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 50, 151-195.

Waterman, D.M. 1965 The court cairn at Annaghmare, Co Armagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 28, 3-46.

Wilson, T. & Gysin, B. 2001 Here to go. Clerkenwell: Creation Books.

Appendix

Sources for cut ups

1) Purcell, A. 2002 Excavation of three Neolithic houses at Corbally, kilcullen, Co. Kildare. The Journal of Irish Archaeology, X1

2) Dronfield, J. 1995. Subjective Visions and the Source of Irish Megalithic Art. Antiquity 69, 539–549

3) Byrne, G., Warren, G., Rathbone, S. McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological Excavations at Rathlackan (E580) Stratigraphic Report. Heritage Council. http://www.heritagecouncil.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/INSTAR_Database/Neolithic_and_Bronze_Age_Landscapes_of_North_Mayo_Progress_Reports_6.pdf

4) Marshall, D.N. and Taylor, I.D. 1976 The excavation of the chambered cairn at Glenvoidean, Isle of Bute. Proceedings of the society of Scottish Antiquaries, 1976-7, 1-39

5) Parker Pearson, M.; Pollard, J.; Richards, C.; Thomas, J.; & Tilley, C. 2006 The Stonehenge River Side Project 2006 Interim Report

http://www.shef.ac.uk/content/1/c6/02/21/27/summary-interim-report-2006.pdf

6) Davies, S. R 2010 The Early Neolithic Tor Enclosures of Southwest Britain. PHD Thesis Birmingham University

http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/1141/1/Davies_S_10_PhD.pdf

7) Caulfield, S., Warren, G., Rathbone, S., McIlreavy, D. & Walsh, P. 2009 Archaeological Excavations at the Glenulra Enclosure (E24) Stratigraphic Report

http://www.heritagecouncil.ie/fileadmin/user_upload/INSTAR_Database/Neolithic_and_Bronze_Age_Landscapes_of_North_Mayo_Progress_Reports_4.pdf

8) Johnston, P. & Tierney, J. 2011 Ballinglanna North 3, Co. Cork: Two Neolithic Structures and Two Fulachta Fiadh. Eachtra Journal 10

http://eachtra.ie/index.php/journal/e2416-ballinglanna-north3-co-cork/

[** If you like this post, please consider making a small donation. Each donation helps keep the Irish Radiocarbon & Dendrochronological Dates project going! **]

If you’re planning to do any shopping

through Amazon, please go via the

portal below. It costs you nothing, but it will generate a little bit of

advertising revenue for this site!

Comments

Post a Comment